Written by Florrie Radio Volunteer Daegan Cockett

I had the pleasure of attending “Before Oasis: In Conversation with Marcus Russell” at the Tung Auditorium on Thursday 8th May, hosted by Dr Mike Jones who is both a professor of music at University of Liverpool and a lifelong friend of Marcus. The night ranged with stories of their shared youth growing up in Ebbw Vale, their love of music, promoting gigs as teens and how this would all be a catalyst for a forty year career as one of the UK’s most successful artist managers, eventually working with Oasis.

Starting the night, Jones sets the scene of their story by sharing pictures of their hometown during their childhood. Black and white images showcase Ebbw Vale in the 1950s, a town donned by a steelworks that at one point would be the largest in Europe, producing steel to be used in the construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge. He speaks of the geographical nature of the location – explaining how it would be unusual as a teen to have any reasoning to venture over the valleys that flank either side of the town and why this seclusion would eventually benefit them.

Jones and Russell begin to talk of their love for music as teenagers and how pirate radio stations were their go-to pass time and source to discover new music that ranged out of the mainstream, usually coming from across the Atlantic. Their love for music that originated from America meant they would regularly order records from small stores in San Francisco to be shipped over. They joke with each other, laughing how this would lead to a postman walking down their road carrying a dishevelled vinyl that had made the eight-week trip to from California to Ebbw Vale. Russell describes his intrigue with this process; “I found myself more fascinated with the distribution of music than tuning a fender guitar”. This, he recounts, signifies how he knew he didn’t want to be a musician from an early age.

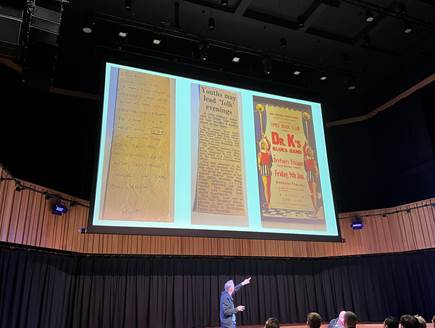

Progressing through his slides, Jones moves on to a series of pictures that give the first significant evidence of how Russell would pave his career.

(Left) A note from Jones to his then girlfriend, asking her to contact folk singers to meet him, to arrange events in the town. (Middle) A snippet from the local newspaper which tells of how these events would become a regular occurrence. (Right) A poster from how these events would eventually form to become “Drifters Escape” – a night in which they would play records in the dance hall below the town’s Municipal Theatre.

Russell recalls fondly how much he disliked the poster that was created at the time. These events would grow significantly as time went on, leading the pair to book bands such as Mott the Hoople. In their first six months, the pair booked another four major acts who would go on to be headliners in the 1970 lineup for what we now know as Reading Festival. As such, Jones would tell of how they would become victims of their own success, tying back to their hometown, and how locals would go on to lobby the Parish Council to shut them down.

The pair talk of these stories and how it would tell them apart. Jones explains how he would want to be in bands, creating music and performing. He shares pictures of himself as a teen in a band – guitars, long hair and a questionable tassel-cladded jacket. Producing the same jacket from behind the chair, the audience laughs as Jones swaps his blue Harrington for the jacket from all those years ago… finding it still fits (possibly more snug than back then)! Russell, in contrast, reiterates his love and interest for “the machine” behind the artists and how this is what lead him to where he is.

Jones would go on to be in the band Latin Quarter, which Russell would go on to manage. The next significant block in the story, Latin Quarter would go on to have success with the hit single “Radio Africa”, which Jones wrote. They talk of how Russell was able to use the valuable knowledge of their events from their youth, to become successful when managing. He explains there were many lessons learnt along the way, but how the principles of what they had done in their earlier years were still the same, just on a different and larger scale. This theme seemed to be prevalent throughout the night; how both had taken their experiences from their youth in a small Welsh town, and how they were able to apply this as they both paved their own successful paths.

We begin to reach the conclusion to the night, as Russell starts dropping familiar names involved in the Manchester music scene. He begins by stating that the band weren’t really on his radar at the time they formed, and that it was Ian Marr (brother of The Smiths’ guitarist, Johnny) who had suggested them to him, as Ian was friends with Liam Gallagher at the time. He explains how Ian had told him that the band had wanted Russell to find a lawyer for them, and after doing so, the lawyer responded saying how the band want Russell as their manager.

This ends as the final piece to the story “Before Oasis” and as they say, the rest is history. Oasis would go on to become one of the UK’s most successful bands ever, with seventy-five million records sold worldwide and eight UK number one albums… returning later this year for their sold-out reunion tour. All in all, not a bad story for two lads from Ebbw Vale, ey?

After the event, I caught up with Mike for a chat…

You talked about your time growing up in Ebbw Vale and the events you would put on. Can you talk a bit more about The Drifters Escape and what it meant to you both at that time growing up and organising these events, but also now in terms of what impact you think it had on your youth?

What has always struck me about growing up where I did was what I was trying to get across in the introduction. I couldn’t really show how confining is a valley town – your physical horizons are very limited so, in a way, your small town really does become ‘the World’. At the same time, through the media you are constantly being made aware of a much wider world, one in which exciting things were happening. For me, all the ‘exciting things’ were musical ones – with the Beatles, all the 60s beat groups and then Bob Dylan as huge things. I wanted to be part of what I imagined they were, and so I began to write songs and play in what would have been called a ‘folk group’, except by then the Incredible String Band had moved all the boundaries in every direction. When the local council gave us an opportunity to run events it meant that we could bring the outside world to us, make contact with it, feel part of it. For me, it meant that one week I would be onstage playing, and the next week introducing a remarkable band, and I was still in school! It didn’t make me a big head, or someone who was swanning ‘round, but it did make me think that, if it was possible to make contact then it must be possible to sustain contact, to be a permanent part of that world. That’s what Marcus became, but I didn’t – there is a world of difference between playing and performing and creating the conditions for playing and performing to happen. That’s what I have been teaching for a long time.

Booking Mott The Hoople must have been an exciting experience too, is there any other notable memories that come to mind from that period?

All of the bands, in their way were exciting to come into contact with, and I was really glad to come across that 1970 line up for what became the Reading festival – to have booked 5 bands big enough to play that festival in our first six months was remarkable, and some of the performances were really memorable – especially Duster Bennett, Mott the Hoople, Pete Brown and Caravan. But what it also showed me was how different ‘styles’ of young people didn’t fit with each other, in the earliest weeks we got a ‘hip’ audience from a very wide radius, but the local lads wanted to fight and that put all the hipper ones off. I think we still have these (class-based) antagonisms – the rise of Reform speaks to that, and, in a way, culture is for marking out your difference not creating a melting pot for everyone to enjoy. I’d need to think about that some more, but it’s weird when music is represented to us as a shared, common space when, in fact, it really isn’t (Oasis speak to this, as well, not that I’m putting them in with Farage!).

You spoke of how growing up in Ebbw Vale and the geographical location of the town offered both some form of isolation, but also a sort of bubble in which you had this time of putting on gigs such as Mott The Hoople as we said, and also the long awaited records you would order from America. Do you think the introduction of social media and things such as Spotify, which allow instant connections with each other and access to music, have made your experiences even more unique and special?

I have to think about this a lot these days, the experiences of my students are now further and further away from my formative ones. The digital world has created conditions I’m not sure the human race is equipped to deal with – on the one hand I can be part of Mr. Beast’s millions of followers, and I can gain validation from this, on the other hand I may be scrolling my phone in a mould-infested, run down tenement owned by a property millionaire (who used to be a drug-dealer, maybe still is) and I have no prospect of a job – I have a (digital) ‘world’ at my fingertips, literally, and yet no real, substantial place in the (material) world. This contradiction is too severe and too painful for us to survive. We all need hope and we all need horizons that we strive (and are supported) to reach, we need to bring back a way of life that concentrates on giving young people opportunities.

You spoke briefly about your time in Latin Quarter and such receiving a note from Paul Weller regarding one of your songs. Does looking back at something like that still excite you as it may have at the time? Do you have any other memories like this from being in the band, playing gigs etc?

Aaaarrggh! I know I should be happy about being in the top 20 and playing Glastonbury and making albums in famous studios in Britain and the USA and all I can ever feel is the desolation that it was over so quickly. I certainly don’t pour cold water on my students, but I do try to prepare them for the psychological demands of ‘putting stuff out there’ and ‘out there’ either hating it or ignoring it! It all goes back to my childhood naivety, that feeling that a ‘world’ existed that I wanted to be part of. I use the Searchers a lot in my teaching. I think they were the best Merseybeat band after the Beatles but what did they have, three years of chart success and then 50 years of cabaret playing the hits?! What I’m saying is, there wasn’t a cohesive world, there was an industry, the music industry, and that is geared to market success, if you’re not a success in the market then off you go, there is a queue of a million waiting at the door. I’m not saying this cynically or bitterly, it’s just a matter of fact. In a way, the Beatles was a grossly misleading phenomenon, because they were so big and so influential, and when you look at it, it was only from Please Please Me to Hey Jude (so just over 5 years), from Brian Epstein’s death (Aug. 1967) onwards, the rifts between the individual members just became bigger and bigger, and so much of their strife was to do with business, with the industry, with how they were managed. I can’t say I’m not glad I caused a pop group to be formed around my songs and that pop group did some exciting things, but it was something I was never in control of and my overall memories are not particularly positive ones.

What sort of music/genre do you listen to? Who are your all time favourite artists/bands and are there any new/upcoming that you currently listen to?

Good questions. We began teaching about the Beatles a few years ago and I’ve found myself going further and further backwards rather than forwards – so I’m now buying 78rpm records of Elvis, Little Richard, the Everly Brothers, Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran, and so on. Outkast, the Streets, Plan B and Janelle Monae were the last wave I caught, I don’t live on my phone and I can’t identify with the post-2007 wave who have kept themselves ‘up there’ by managing their social media presence. I sound like a grumpy old git but I’m still more likely to listen to Bob Dylan than anyone else.

A massive thank you to Mike for both the event and his time afterwards, it was extremely enjoyable and interesting to hear his stories.

Oasis Guitar Charity Raffle: Win a Guitar Signed by Noel Gallagher!

We’re thrilled to announce an exclusive charity raffle to win a guitar signed by Noel Gallagher, legendary lead guitarist and songwriter from Oasis! This incredible opportunity is part of our effort to raise money for The Florrie and support the preservation of our Grade II Listed Victorian building, a cultural and community landmark.

Raffle Details:

- Grand Prize: A guitar signed by Noel Gallagher from Oasis

- Ticket Price: £5 per ticket

- Drawing Date: 4th July 2025 – the day of Oasis’s first reunion gig!

- Location: The Florrie, 377 Mill Street, Liverpool L8 4RF

How to Enter:

- Online: Purchase your tickets on our website https://theflorrie.bigcartel.com/product/oasis-guitar-charity-raffle-win-a-guitar-signed-by-noel-gallagher.

- In-Person: Tickets are also available at reception in The Florrie.

All proceeds will go directly to preserving and maintaining The Florrie, keeping this historic space alive as a social, cultural, and charitable hub for Liverpool’s L8 community.

Get your tickets now for your chance to own a piece of rock history and support a fantastic cause!